As the Rolling Stones tour North America this summer, only three of the original five members will still be in the band. But those three, most people would agree, are the essential core: singer-songwriter Mick Jagger, guitarist-songwriter Keith Richards and drummer Charlie Watts. The second guitar slot has changed over twice—from Brian Jones to Mick Taylor to Ron Wood–and retired bassist Bill Wyman has been replaced by non-member Darryl Jones. But few would dispute that this is the genuine article.

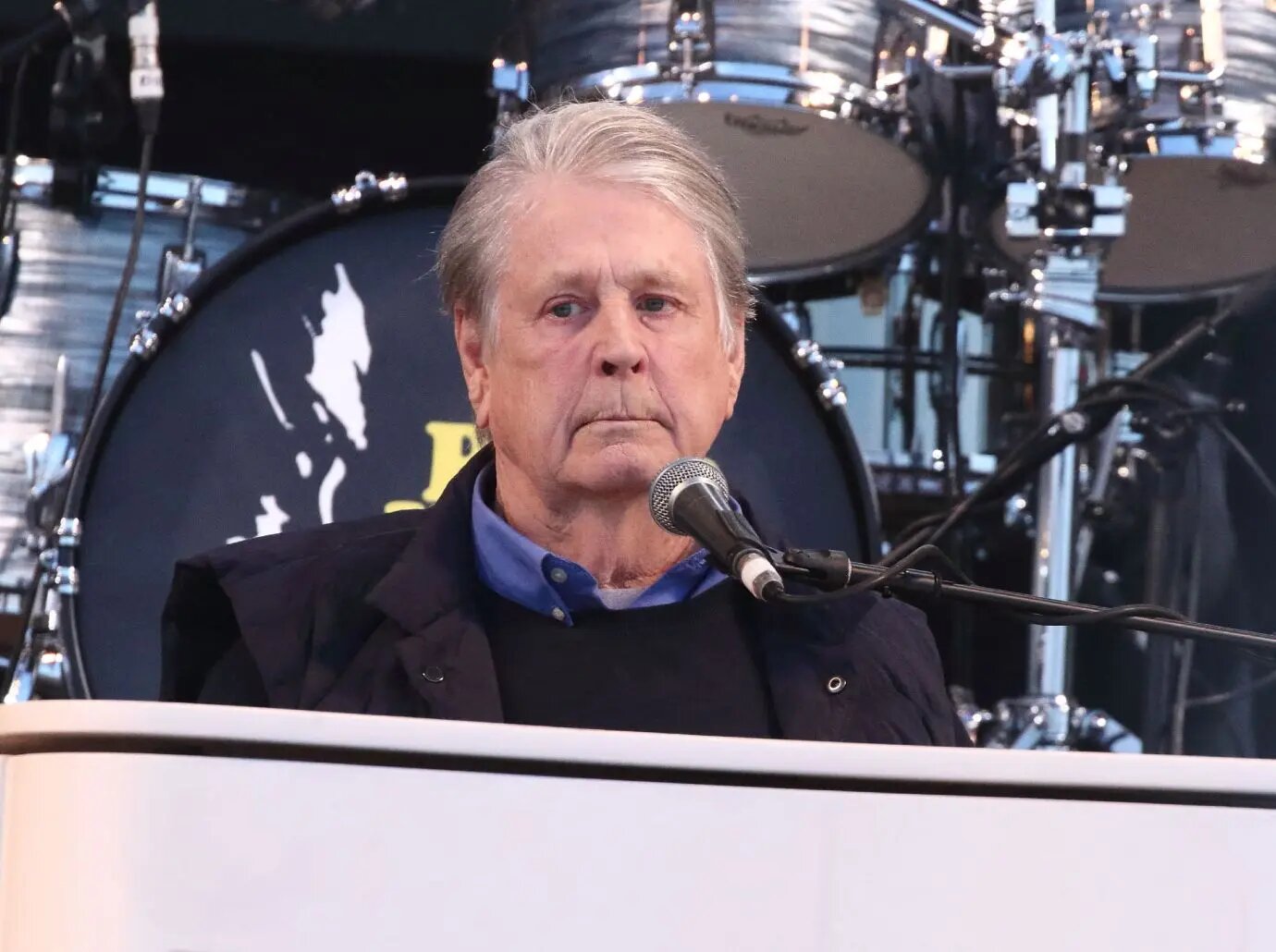

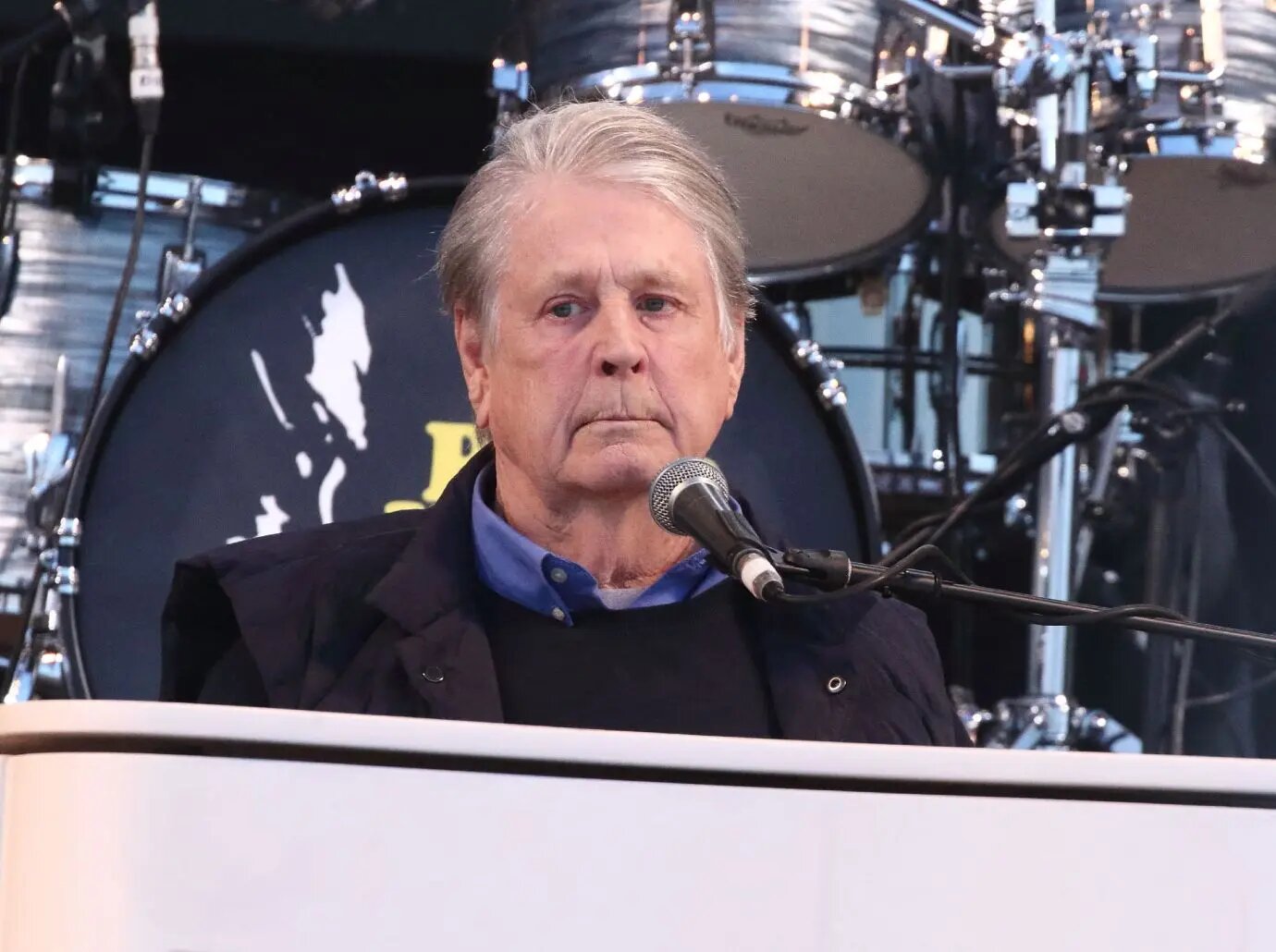

The Beach Boys are also touring, but only one of the original members will be on hand: lead singer Mike Love. Two of the original five (brothers Carl and Dennis Wilson) are dead, but the other two surviving members (Al Jardine and third brother Brian Wilson) will be touring this month under the Brian Wilson banner. Love will be joined by another longtime Beach Boy, Bruce Johnston, but Wilson will also have another former member, Blondie Chaplin. So why does Love get to present his show as the Beach Boys, when Wilson, the group’s chief songwriter, secondary lead singer and producer, can’t?

Love would explain that he has the legal rights to the name, and he would be right. But if we view the situation not from a lawyer’s perspective but from a fan’s, it’s clear that Wilson deserves our allegiance. And this raises the questions that every fan must confront sooner or later: What gives a band its identity? How much can you change its personnel before it’s no longer the same band?

Early in my music-critic career, the Washington Post sent me to review the Marvelettes, the female Motown trio that had its first hit in 1961 with “Please, Mr. Postman.” It didn’t take much investigation to learn that the 1983 version not only contained no members of the original group but also no members who were old enough to read when “Please, Mr. Postman” was first released. It was a scam operated by promoter Larry Marshak, who had registered his right to the name after Motown dropped the group. The former members sued him, but it wasn’t until 2012 that the original members’ heirs finally prevailed in court. In 2007, California became the first state to pass the Truth in Music Advertising Act, soon followed by other states.

That clarified the legal issues, but what about the artistic question: How much can a band change before it no longer deserves our attention? Is a music group more like a baseball team that changes so gradually that it retains our loyalty no matter who’s on the roster? Or is it more like a basketball team, where the departure of one superstar such as Lebron James can dramatically alter the identity of the Cleveland Cavaliers or Miami Heat?

We usually link the identity of a band to its lead singer and/or chief songwriter. As long as that person is still around, we’re willing to accept a new drummer or new keyboardist. This may not be fair, but it’s true. Keith Moon and Tiki Fulwood were great drummers before they died, but we’re willing to accept the Who and Parliament-Funkadelic without Moon or Fulwood as long as Roger Daltrey and George Clinton are on hand. But once that key voice is gone, we usually lose interest in the band.

John Lennon, George Harrison and Ringo Starr might have been able to carry on as the Beatles after Paul McCartney quit, but it seems unlikely that audiences would have accepted Harrison and Starr as the Beatles if both Lennon and McCartney had left. It would have been foolish for Dave Grohl and Krist Novoselic to go on as Nirvana after Kurt Cobain committed suicide in 1994. Wisely, they didn’t, and Grohl launched a new band, the Foo Fighters, with its own identity.

But it’s not impossible for a band to survive the loss of a lead-singer-songwriter if they handle it properly. Witness the quick sellouts for the farewell concerts by the Grateful Dead this summer. No one disputes that Jerry Garcia, the singer-guitarist who died in 1995, was the band’s linchpin. But fans recognize that the band was not only a musical democracy but also the binding glue of a community larger than any one person.

Leave a Reply